|

Joanna Craft is a jewelry maker from California specializing in metalsmithing and enamel. Her works are aesthetically beautiful, joyful, and elegant, perfect for any outfit or occasion. I was fortunate enough to interview her about her career as a jewelry maker, I hope you enjoy reading!

As always, I first asked Joanna about the effects of the pandemic on her work and business. She told me “COVID-19 has had an immense effect on my jewelry business. All of the orders that I wrote at the American Handcrafted trade show in January 2020 were cancelled or postponed after March 13, except the ones that shipped in February. I normally would have been filling and shipping orders from Feb -Sept. I worked on some new ideas in the first few months of the pandemic, but it was hard to stay motivated to create new pieces. I found other ways to occupy my time, such as gardening, hiking, kayaking, pottery and projects around the home that I never had time to do. It will take more time for things to return to normal, but I’m looking forward to being back in my studio full time. My jewelry practice has been a joy, even with the challenges of the past year and I still look forward every day to being in my studio.” We’re hoping things return to a similar normal for Joanna and her small business soon. In the meantime, it sounds like this pandemic has offered time to explore and do things that working doesn’t always allow for, which sounds like the best situation possible! Next I asked her how she got started making jewelry. “I started making jewelry in high school. I started out in college as an art major, with an emphasis in metalsmithing, but I switched to landscape architecture. I had a long career as a landscape architect/planner, but always made jewelry on the side. I made the decision in 1999 to make jewelry full time and have never regretted it.” One of my favorite things about interviewing artists is hearing the path they took to get where they are today. Often the road involves several changes and periods of exploration, trying to find out what speaks to them and what they could see themselves doing for a long time. I’m also partial to artists who have worked with the landscape, and enjoy the forms, textures, and colors they take with them once they move onto the next art-making thing. It’s powerful to hear Joanna bold in her conviction to make her life about art-making and not regretting that choice. All very inspiring! After hearing about her start as an artist, I asked Joanna about what keeps her inspired to create, what ideas and images are her starting point when making work. “My jewelry reflects my interest in the natural world and architectural forms, with a textural, organic feel. In the past few years, I have also added enameling to my work. I’m passionate about traveling and draw inspiration from ancient cultures and from the natural world. Texture, color and pattern define my work.” I enjoy the breadth of creations derived from being inspired by nature. It’s exciting to see the different forms inspiration can take, because it relies on the artist’s own sensitivities and interests. I’m interested in Joanna’s zoomed-in inspiration, especially with working with small pieces like jewelry. Containing the vastness of nature is a task, and textures, color, and patterns can distill vastness into something small, simultaneously displaying the micro and macro found in nature. Her previous work in landscape painting and metalsmithing shows this dedication to distilling and abstracting nature down to simpler, pocket-sized forms, which takes a lot of work! So cool! Talking about inspirations in Joanna’s work led us to discussing her creative process and her art community. “I keep notebooks of sketches of ideas for pieces, but in a lot of cases, I just start working with the metal and ideas take shape. I work primarily in silver and other metals and start with sheet and wire and, using traditional metalsmithing techniques, such as sawing, forming and shaping, texturing, soldering and enameling, manipulate the metal. Sometimes a piece starts out as one thing and turns out as something unexpected. That’s the fun of fabricating with metal. The enamel is kiln fired. I work alone in my studio, but during normal times, I have a community of fellow artists that I see at shows and events. It’s a supportive group of people and I miss being around them. My husband, family and friends have always encouraged me.” As a person who has never worked with jewelry or metal before, I was surprised and intrigued to note that metalworking can involve a kind of spontaneity like other art forms. I like imagining the ways that material can inform and change a piece, it’s a practice that is very grounded in the physical and visceral, the felt experience and material reality of art making. The idea of crafting things to be worn and imbued with personal and individual meaning is very hands on and grounded in the tangible, and it’s nice to see that translation of the material process carried over into the final product, these personal items people can wear. Finally, I asked her what experience she hopes the viewers gain when they interact with her pieces. “My goal in making jewelry is to create timeless small works of art. I see jewelry as a means for the wearer to express their creativity and personality. Craftsmanship and ease of wear are important.” Her pieces act as a vessel for the owner’s creativity and personality while holding their own uniqueness and charm, goal fulfilled! If you want to check out more of Joanna’s gorgeous work, you can browse her Facebook page here. Thank you to Joanna for answering my questions so thoughtfully, and thanks to you, reader for reading! Best, Louise

1 Comment

Lynette Lombard is a local painter and professor at Knox College. Her work explores the landscape and feeling a connection to place and the natural world, translated through the medium of plein air painting. I have had the fortunate experience of being a student of hers for 5 years now, and get to see her wonderful way of viewing art and the world firsthand. Her paintings are thick and expressive, full of viscerality and imbued with feeling in each stroke. I enjoyed flipping the script and asking her questions for a change!

I started out by asking Lynette how COVID-19 has affected her art practice, especially as a professor during this time. She told me “After teaching remotely in the hectic early days of the pandemic in the spring, I felt such an urgency and hunger to paint. All term I had painted out my studio window and then at the end of the term I drove out to Green Oaks. I found being out in nature gave me energy and took me into a world of wonder and discovery. The isolation was liberating in the sense I had more time to paint, but COVID has brought a profound sense of loss and urgency into our lives and into my paintings. It has been an anxious time, especially during the elections, and throughout 2020 I lost a few dear friends. At times, the grief and the anxiety have influenced my work.” The effects of this tragic pandemic cannot be understated. As people intimately tied to cultural and political happenings, artists have always imbued the surrounding historical context into their work. It’s safe to say this is one of those times in which art is extremely important, as an historical record of both the events and feelings of this time, and a method of healing and helping. We are heartbroken to hear the effects of the pandemic on Lynette’s personal sphere of loved ones, and hope that her art is helping her to process the grief and anxiety experienced during this time. Shifting now to the particulars of Lynette’s practice, I asked her about her process, specifically her methods during plein air painting. What does she look for in the landscape that captures her attention? How does she paint those interesting moments? “I look for places that move me, for a challenging complexity, a structure that is dynamic and a place where color, space and light evoke drama. I work mostly from perception, which opens my imagination as I work to capture several moments in time and in space. First I draw to understand the main visual structures I see. Then I begin to paint, at first descriptively, the image begins to take shape and build into a volumetric space, evoke feelings and the painting takes on a life. There’s an elemental embodied physicality that I feel with paint- pushing it one way then another, scraping it, feeling its mass, fragility and fluidity. This process makes me feel alive, out there experiencing the elements, part of something bigger than myself. I organize all of these multiple moments into one distilled image by bringing the painting into the studio and working on it, then going back out again.” The importance of integrating drawing into an artist’s practice often comes up when Lynette and I talk. I asked her about her personal relationship with drawing and the dialogue it creates in her work. How do drawing and painting overlap? Why is drawing important? “I think drawing is at the core of my work. I’ve always been interested in structure-- the scaffolding or architecture that holds the whole work together. I find drawing so direct. All you need is a pencil or charcoal, an eraser and a piece of paper. It’s immediate and I can make changes quickly. Because drawing is about the bare bones of a painting, I draw initially from a motif or when I draw from one of my paintings when I’m stuck, I find clarity about what I want to happen. Drawing helps me see clearly.” I see this play out in her work, particularly in the big geometries and planes that move through the space in her landscapes. Drawing holds the other elements in her pieces like color, brushstrokes/marks, and shape together. I like Lynette’s remark about drawing being so direct, it’s a very bodily and visceral practice that’s felt, following lines and marks and feeling their movements. Drawing the landscape becomes a direct interaction with the terrain, the different planes corresponding to the ones we traverse, both with our bodies and our eyes. The topic of drawing led us to discuss the visual elements that excite Lynette, such as line, shape, and color. “I see every shape as a force not a thing. I see big masses of sky with clouds tilting in one direction, while the trunks of trees move in an opposing direction and the land pushes up as the tree pushes down. I feel as if I’m juggling the interval shapes, the shapes of forms, directional forces, a deeper space, a shallower space- all these forces are moving in relation to each other. Painting is like a dance. Paintings never turn out the way you think they might and that’s a challenge and an excitement. I am painting the life forces at work poetically, visually and viscerally.” Lynette’s comment “I see every shape as a force not a thing” has helped me out in my own practice as an artist. Often, landscape artists think about shaping the experience of a particular place/part of nature as a form with color, light, and texture, not as a nameable thing. Shaping is about really looking and observing, seeing what is actually in front of you, and distinguishing the experience from preconceived notions. Juggling elements of a piece based on their different or similar forms, colors, shapes, volumes, etc. really is the exciting part--finding ways to relate and distinguish forms based on what you wish to accomplish in a piece. Often in my classes with Lynette students are assigned obstructions. The idea is to shake up your habits, and get you moving outside of your normal routine to add something new or fresh in your work. Obstructions are particularly helpful when you feel stuck in your practice. For example, if you consistently use green in a piece, you might be assigned the obstruction of using its complementary color, red, instead. I asked Lynette how she keeps her practice interesting. What are things you do to switch it up if you fall too much into patterns? What are some obstructions you set for yourself when necessary? “Each painting provides a different set of problems. The psychological frame of mind I’m in makes me receptive to different points of view. Sometimes, I paint looking down into the valley, or I prefer to look up at the craggy tops of mountains, or I want a dense intimacy, or an expansive openness. I switch the complimentary colors so a green field becomes red. And I also paint at night. I switch from painting to drawing. I have so many ideas for paintings I can’t keep up, but at times in the winter for example, I make drawings from artists’ works that influence me. In doing this I see how certain artists create a diversity of rhythms and complexities and manage to unify the whole painting.” Speaking of these artists Lynette draws from, I asked her more specifically about her art influences in her work. “Soutine, Constable, El Greco, Courbet, Joan Mitchell, Marsden Hartley, Jane Culp, Auerbach and my husband, Tony Gant. Soutine, Mitchell and El Greco’s rhythms are wild and so intelligently integrated into the subject matter of a painting. Courbet and Constable have a beautiful sense of weight and this is also true for Auerbach, especially how he handles paint as a visceral material substance that shapes the volume of what he paints. Hartley and Culp are so specific about the planer solidity and volumes of what they paint in the landscape. Tony Gant has the most perceptive and unusual insights and has a great eye. I often think paintings can move us across barriers of time and are alive today, albeit in different ways from when they were made. I always say to my students that we all have art families we are part of, and that we connect with them across time because we share sensibilities. My former teachers have also been my guides- Nick Carone, Andrew Forge, Frances Barth in the US; Basil Beattie, Harry and Elma Thubron and Bert Irwin in England. And my friends- artists, writers, translators, theater directors, architects, poets and myriad friends who make me think about things in a new way.” After speaking about those who taught her, I asked her about how teaching others informs her work. “Teaching is unpredictable, it demands a clarity in terms of explaining an idea or a series of complex ideas. I am always challenged by my students, I like the dialogue I have with them, the exchange of ideas and experiences. I do bring my experiences of painting to the classroom, but I try not to bring the classroom into my practice. However, there are times when a student’s work or a conversation with a student speaks to me and makes me rethink an idea in my work. There can be a back-and-forth at times, a reciprocity, between teaching and my own painting. Making my own work throughout the term keeps me in touch with the frustrations and challenges that students encounter as they make work. I think all art making and teaching has to involve a sense of discovery. As an artist and a teacher, I work to stay connected to current artists and to discourses around historical works as well as contemporary practices.” As her former student, I can attest to the importance of this dialogue between professor and student. Lynette is particularly adept at bringing an enthusiasm for discovery in art, engaging students to use their art-making tools as extensions of their bodies that will help them bring their experiences into a visual medium. I am constantly amazed and interested in her point of view, the ways her mind moves in response to students’ work, how she situates herself in the experiences students portray through their work, and the clarity of language she brings to those felt experiences. This is particularly powerful because she invests time in understanding students’ point of view, and deeply cares about what they want to say through their art. Finally, I asked Lynette what experience she hopes viewers have with her work. “I hope my paintings will take viewers into an elemental experience of being in a place. I hope they’ll feel the spirit of a place. Hopefully, a viewer will recall places they remember and feel connected to something larger than themselves. There’s an urgency to painting the landscape today. I feel as if I’m painting the nature we are losing. My paintings become memorials. In the long run, I think landscape paintings can offer a feeling of recognizing that place matters and where we are shapes who we are.” The best parts of experiencing any kind of art is sharing in the artist’s point of view, and finding how we as the viewers can relate and bring our own experience to the work. Through her dedication to depicting a felt experience, and being empathetic towards the subject itself, Lynette’s paintings achieve the sense of wonder and experience of place she hopes to achieve. How truly wonderful! If you want to view more of Lynette’s work, stop by our gallery space and check out her website by clicking here. Thank you Lynette for this wonderful interview! I hope you enjoyed reading! Best, Louise Justin Rothshank and Brooke Rothshank are the team behind Rothshank Artworks. Justin makes the beautiful pottery pieces with political figures that grace our shelves, well-crafted keepsakes of prominent U.S. figures. I was able to interview Justin about his pottery and influences, and a great conversation ensued. I hope you enjoy reading about his work!

The effect the pandemic has had on Justin’s art practice has largely been shifting his schedule to accommodate his family’s routines. Additionally, he’s found that “demand for political themes in pottery” has seen a decrease not just this year (though the pandemic has amplified it), but since 2019. As representing political figures has been a part of his practice for 12+ years, this means a shift in his work. Hopefully this year brings room and time for exploration! I asked Justin what has influenced his work throughout his time as a potter. “I'm influenced by my Mennonite background relating to themes of simplicity, nonviolence, hard work, and respect for handmade trades.” I like these values as a backdrop to his work, they make me enjoy his pieces even more knowing the intentions behind them. Justin also has a section on his website in which he acknowledges the stolen land of the Potawatomi he lives and makes art on. Though he doesn’t specifically cite the Potawatomi as directly affecting his art, I think they influence his work in terms of the respect he speaks of, acknowledging those you are in community with, past and present. He also spoke of his influences early on in his career. “My high school art teacher was instrumental in encouraging me to pursue clay. She introduced me to raku firing and wood firing, which was very appealing to me. The process has always been something I greatly enjoy.” Next I asked Justin about his process. “I was interested in addressing themes of social justice in my work, and thought about the possibility of text transfer as a way to do this. I took a workshop at Anderson Ranch in 2005 on image transfer with clay, and from that began to develop my own style which includes building layers of imagery, texture, color, and glaze. I use an electric potter’s wheel that is set upon a stand that I built. After each piece is created it is fired unglazed. Generally, each piece is then dipped in liquid glaze and fired for a second firing. Then each piece is decorated using a variety of ceramic decals. I find these decals from a multitude of sources, and some are custom designed and printed in house. Some of them I design myself and have printed by custom print shops, some I purchase from commercial manufacturers, others I acquire through eBay or from friends. I have sourced decals from China, Australia, Denmark, South Africa, Great Britain, and the United States. During this stage I might also hand paint some pieces with Gold, Silver, or Platinum luster or China paints. Usually I layer decals and fire pieces for a 3rd, 4th, or 5th firing, or more, to achieve a layered, collage effect.” I am very interested in artists across all mediums using collage techniques in their artistic process, both through gathering influences and physically manipulating materials. Most art is created through a collage-like process, gathering influences and techniques from multiple sources and putting them together in a unique and engaging way. His addition of 2D techniques to his 3D practice feels just that, as well as a way to evoke the pictorial and objective simultaneously in his work. Justin is passionate about his practice and its effect on the communities he participates in. He believes in collaboration and teaching others, and I asked him more about what these practices mean to his work. “Education is a big reason why I choose to put political faces on my pots. There are many figures, past and present, that are unknown to our larger society. Adding these faces to pots helps begin a conversation that can lead to furthering education. I've always shared about my process/techniques. It has helped me in connecting with other artists, and solving process related problems with my own work. This has been incredibly valuable in enabling me to continue learning at a rapid pace.” I think this is a sentiment shared by many educators and teachers all over, that teaching others helps them learn as well. It becomes a cycle and a shared space of learning from one another, which is what collaboration is all about. A part of Justin’s practice is writing about themes in his artwork that challenge and inspire him. One such piece he wrote is about what collaboration means to his work, which he graciously shared with me. I enjoyed the parts in which he described the culture of collaboration he’s immersed in, and what this community fosters in his art. “I love the shared risk of collaboration. I’m interested in the failures, the tests, and working through a process that isn’t always comfortable. I’ve grown up in a local Mennonite tradition of collaboration. Craft and labor projects, in the historic Mennonite communities, are often a collaborative environment. Barn-raisings, quilt making, food preparation all require a spirit of collaboration, work, and craft. My life experience includes many of these experiences, which feel both familiar and comfortable. My extended family grew up on rural farms where joint work efforts were daily occurrences and I currently live in a rural area surrounded by Amish farms.” His remark about wanting to exist in a creative space that isn’t always comfortable but has a foundation of trust and familiarity is poignant. The interplay of comfort and discomfort is integral to the art-making process, feeling familiar with something and using that as a bridge to connect to something unfamiliar. It’s great to see community as the source from which these contrasting elements emerge for Justin! If you want to know even more about Justin, Brooke and their practice, check out their website! It has a bunch of resources and writings by Justin about some of the topics we covered in this interview, such as teaching and collaboration. You can visit their website here. Thanks for reading! Stay safe and healthy, Louise Patrick DeJuilio is a relief artist, making paintings that move into the realm of sculpture. His works feel still and quiet, formed by the passage of time. They are stunning renderings of dilapidated barns, houses with exposed drywall, and spaces under staircases. There is something magical about the combination of stillness and the buzz of time each of them hold. I feel very lucky to have interviewed him about his process, and I hope you enjoy reading about it too! Patrick told me that the effect the pandemic had on his work is less productivity, which makes sense. Whether it’s not being able to find a space to work comfortably and for concentrated periods of time, or finding it hard to sort through the wide-spread anxiety and depression so present right now, it is difficult to be generative! After inquiring about the pandemic, I asked Patrick how he came to this body of work, and what in particular interests him about making reliefs. He told me “For several years I was a carpenter, and worked with architects, masons, and other tradesmen. I appreciated the details in the buildings that they created. My original ideas for my 3D wall art started with the materials I collected from my job working for an adhesive company. I saw that I could make these materials look like something else on a different scale. Sheets of particleboard could be cut into small blocks that looked like bricks, corrugated cardboard became tile roofing, strips of veneer became siding or flooring. I decided to make my first piece using only these scrap materials and different adhesives our company manufactured. I even used various colors of glue as paint. I have since incorporated paint and plaster.” Next I asked him how he begins and ends each piece. “A piece will start with a lot of planning. Create an interesting arrangement of shapes that become doors, windows or stairs. I carefully choose materials that have the dimensions and are the proper scale for the composition. Then I build my canvas that is then painted or papered to achieve the appearance I am looking for. I found this to be more challenging than to just paint a flat painting with false perspective. I have a pretty good idea of the finished piece in my mind when I start because it isn’t easy to make changes due to the 3D surface of my canvas that is already established. At times I’ll make color scheme changes, but for the most part the composition is unchanging. Occasionally I'll change the direction I see the light, coming from the window or doorway rather than the recesses falling in the shadows.” His careful attention to detail and naturalism is evident in the final product. It’s impressive that he sets up a formula from the start that doesn’t allow for wiggle room or change in its goal. There’s a lot of skill and control involved in that approach, especially if the colors change halfway through, as color is a powerful compositional tool that can affect depth and flatness in a piece. Lastly, I asked him about the time aspect of his work. “I find the time-worn aspect is more interesting and has more character. It is more interesting to make things look old in different ways. Time is merely the patina on the objects and places that I depict in my work. Aging is an observation that I have always found interesting, be it people, places or nature. It inspires questions, where is this? What happened here?” I enjoy asking these questions myself as I gaze at his pieces. The empty spaces and worn-down appearance creates a simultaneous sense of emptiness and fullness, giving the viewer an impression of time that moves non-linearly, containing all that happened and all that is left. If you want to check out more of Patrick’s work, you can browse his website here. We are excited to see where Patrick goes with his work this new year! Stay safe and healthy, Louise Happy 2021 everyone, we made it! I hope this post finds you well and hopeful for the new year! Larry Jon Davis is an abstract painter that delights in color relationships. His pieces carry a sense of time, depth and texture handled deliciously through ambiguous figures and spaces. I really enjoyed talking to him about his art, and I hope you enjoy reading about it! As I do with each artist, I asked Larry about the impact the pandemic has had on his work. “COVID-19 has represented a kind of two-edged sword with regards to my art. On one hand it has dramatically limited my face to face interaction with other artists, exhibitions and museum opportunities. On the plus side, however, it has encouraged me to spend additional uninterrupted studio time, and to evaluate how I really want to be remembered stylistically as an artist.” It’s great that Larry has been able to use this period of uncertainty to spend time with his practice! It is hard work to truly be present with what you love right now, but it’s work that doesn’t go unrewarded. I have personally been very inspired asking artists how they’ve moved through this time, seeing their willingness to stick with their craft because it’s something that pulls them through, and seeing those that take a break. Whatever the case is, it’s nice to hear personal accounts of struggle and triumph that we can all relate to and learn a bit from, especially during this time of finding new ways to connect and engage in community. To begin our interview, I asked Larry how he starts each piece. “Since color is such a prime consideration in my work, I often block in a canvas or a panel with the opposite hue with which I hope to finish a given sector of a composition. That gives the piece a “peek-a-boo” effect---bits of the correct color showing through the final layer. Atop this first layer I add a horizon line that usually winds up in the upper third of many of my paintings. The final thing that happens at the start of a work is a freely gestured balance of rectilinear architectonic marks in harmony with curvilinear organic marks. In a subtle way these right angle marks pay homage to the edges of the square or rectangular canvas, while the curvilinear marks envision a figurative or floral content. After that it is almost always a path that has a life of its own.” I enjoy the layered color in his pieces, it gives us a sense of the beginning and makes the works feel layered in time as well as color. Texturally it’s a lovely and engaging technique as well, it gives the blocks of color more density and depth, and gives the viewer a sense of Larry's process, groping and searching for particular forms and colors. Larry identified texture as integral to his work, as it relates heavily to the materials he chooses when he sits down to paint. “I have always admired painters whose works look good both from across the room as well as at arms length. One of those desirable up-close aspects is texture, and that is often measured in the generosity of paint and the bravado with which it is applied. Now that I have added cold wax medium to my oil painting method I am able to utilize many additional tools beyond that of conventional brushes. I can create a range of texture using squeegees, rakes and combs that enable even more bold effects.” Next we discussed the biggest interest and influence on his work, color. “After nearly seventy years of painting I think it is fair to say that color holds the most enduring interest of my creativity. Having taught color theory in my days as a professor, I always tried to emphasize how important it is to recognize what is the opposite or complement of any given hue, be it bright or dull, dark or light. That means on a color wheel every bluish hue has its opposite orangish counterpart, and so on. An allied color concept that I make use of is that of simultaneous contrast. Here, if one uses a bright green next to a bright red, we make each hue look more intense. Ironically however, if we mix the two colors together, we get an infinite range of browns. The importance of this principle of opposite colors is that it provides a kind of harmony to a painting as it does in the natural world around us.” As someone who is drawn to the high contrast relationship between complements, I understand the sense of harmony and push and pull they can bring to a piece. In Larry’s pieces I see that simultaneous tension and harmony they provide, moving spaces forward and back, constantly in flux. This movement of push and pull in his pieces follows in the tradition of other abstract painters such as Hans Hoffman who utilized color to manipulate space. We talked further about the compositional strategy of push and pull with regards to the cubist-esque forms he uses, and how that influences the figure-ground relationships in his ambiguous spaces. “Most realistic work often makes use of a range of visual tricks like shading, overlap and relative size to convince the viewer that a given two dimensional shape is really a three dimensional form. Sometimes however, especially in more abstracted approaches like my own, it is fun to withhold those clues so that a kind of ambiguity can exist. Cubism often emphasized the importance of shape over form.” I like that his forms slide and move into one another, sometimes hitting each other, giving the piece a collage-like quality. Our discussion of forms and how they move through his pieces led us to a discussion about scale. “I find it interesting to consider how tastes in art change over time. As a college student in the 1960’s, the prevailing thought was that a decent scale for a serious painting was the distance of the arc of the fully extended arm. The 5’ to 6’ paintings provided an impact by their very presence. A larger work like this also encouraged a freedom of brush stroke and mark making that is almost impossible to achieve at a smaller scale. One of my challenges of working smaller, as current taste seems to desire, is to retain this visual spontaneity. Another challenge I have encountered over the years is not to yield to the temptation of making paintings that always show too many small objects within a more panoramic composition. On a trip to Walden Pond a few years ago I bought a small poster that hangs high on the wall of my studio. It says, “Simplify, Simplify.” Lastly, I asked him about the experience he hopes his viewers gain from his work: “I hope that viewers of my paintings will come away with an appreciation for their complex colors, textures and purely formal considerations. Though many of them have recognizable elements, it is equally important to me that they convey a freely abstracted interpretation of many decades of observation--travel observations from Mount Fuji to Rome’s Colosseum, from Trafalgar Square to the lakes of Northwest Ontario. Combined with decades of figure drawing, these seemingly disparate sources have given me a reverence for both natural and human made environments. Never successful at protest or political art, I have spent a lifetime chasing some kind of aesthetic summed up by the sight of a sunrise on some Midwest prairie.” I certainly enjoy the visual journey I am taken on when viewing Larry's works, and enjoy the opportunity they provide to enhance my own visual language! If you want to see more of what Larry’s been up to, check out his portfolio online here. A big thank-you to Larry for the wonderful conversation! I’m excited to see what 2021 brings for you and your work. Best, Louise Jenny Nunnelee of Lakestone Jewelry crafts beautiful pieces with stones and driftwood collected from the Great Lakes Minnesota area. She has been making jewelry professionally since 1999. The act of collecting the stones and pieces of driftwood is integral to her craft, and reminds the buyer of the meditative experience of being on the beach, gathering objects of interest. We are lucky to host a Trunk Show of her pieces in our shop this week, so stop by and check it out in our shop or online!

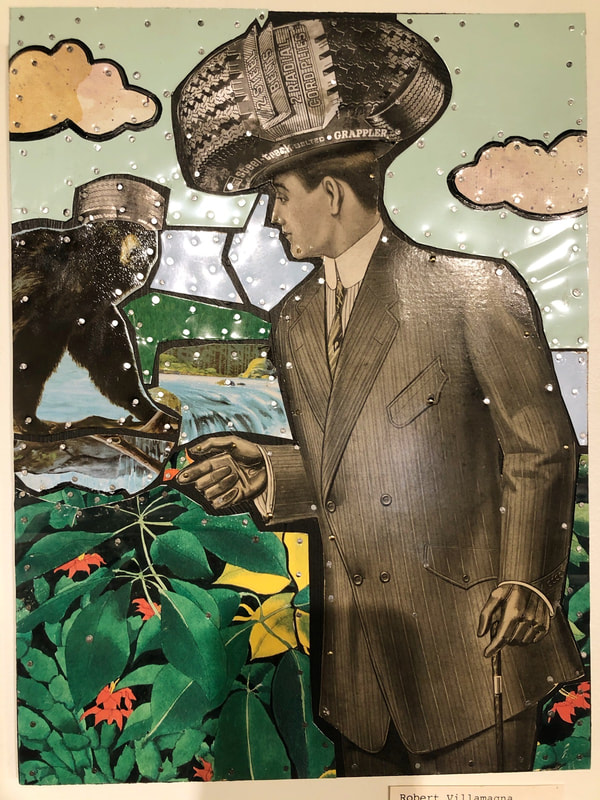

COVID-19 has certainly put a strain on our lives, and it’s no different for artists. Like many who are struggling to find work or make money right now, artists are having a tough go of it. We really hope you take the opportunity to shop at our store and support independent artists no matter what’s going on in the world, but especially now when we all have to help each other out a bit more to stay afloat! I asked Jenny how her business and creative process has been affected by the pandemic, and she responded: “In a normal year I travel all around the country full time, doing art shows. They were all cancelled this year. I decided to take advantage of the situation and spend the summer at Lake Superior. I worked on other creative projects, made masks, enjoyed the outdoors, but didn’t make jewelry. My husband who works with me is immuno-compromised so it was good to keep him away from people. We were lucky enough to get unemployment which helped. Now we are focusing on selling online. Hopefully we will be able to do art shows again someday.” It’s nice to know that COVID-19 has still provided Jenny with a creative space to move through this difficult time, even if it’s a departure from her normal work. I hope for Jenny and all other independent artists some new semblance of normal can be found soon, and that they can find new ways to connect with communities interested in their work. That’s what we hope to achieve here at Dovetail! Jenny is from Minneapolis, Minnesota and frequently visited Lake Superior as a child, so the place and the stones hold special meaning for her. “I’ve always been a fan of found object art and always made jewelry, so when I found rocks small enough to make jewelry with, I couldn’t help myself.” I asked her what particular attributes attract her to the stones she finds on the beach, and she told me: “I look for small, smooth, flat rocks. They need to be fairly thin, as weight is an issue. An ideal skipping stone is good. I like ones with lines or layers. Almost all are used as is. They might get drilled or cut in half but I rarely manipulate the shape. I try not to be too literal or too figurative, I prefer to just use the lines and leave them a bit abstract.” Next, I asked her about her material process--what she does with the stones and wood after they’ve been collected. “I only work with sterling silver as a metal. I manipulate sheet metal and wire using heat and force depending on what is necessary. I’m a bit of a tool junky, they have overgrown my studio into my living room area. We have a diamond-blade rock saw, a diamond drill bit, and a drill press used to cut the rocks, though I prefer to work with the natural shape of my materials. Sometimes I start with an idea and sometimes I get my idea from the found item. Sometimes I will drill the rocks and sometimes set them depending on the design and on how fragile they are. I’ve also been using a lot of driftwood lately but rarely alter that either. ” I love the care and attention given to the objects she finds, leaving them as she found them. There’s a profound sense of collaboration with nature in this act, and I love that Jenny wants to work with nature so closely. I’m always curious about what lights the creative fire under artists to get going and start making, so I asked Jenny what motivated her to start making jewelry in the first place. “I’ve always made jewelry, but my junior high school had a wonderful art program that had a large jewelry section. When I was older and trying to figure out what I wanted to do, I decided I’d like to make more jewelry and see how that went. I went to Minneapolis Technical College and have a diploma in jewelry manufacture and repair. I owned a bead store briefly but that didn’t work out, and I figured if I was going to make a real go at jewelry I better get on it. I love found object art and found some rocks I could use and had a good source for many. Plus, my husband was also into it, so it was something we could do together. He works for me-- drilling rocks and helping with other things. I decided to see how far I could take it, and 10 years later I’m still going!” Lastly, I asked her about her motivation for making these pieces -- what they mean to her and what she hopes they mean for others. “I’ve always made jewelry, from when I was in grade school, it’s always appealed to me. I prefer functional art, even though jewelry doesn’t provide a practical function other than adornment. Wearing items of adornment that appeal to you seems to be something that people have enjoyed since our cave dwelling beginnings.” “I don’t have a deep meaning I convey with my work. I prefer the owners to attach their own meaning to the piece as they are the ones who live with it. I just hope people find it beautiful and interesting and calming.” I certainly feel calmed by her stone pieces! As someone who is also from Minnesota and has visited Lake Superior a number of times, I appreciate the nostalgia the pieces provide as well as a translation of the experience of walking on a beach and collecting stones. There is a very particular sense of calm that comes with the beach and objects associated with it, a much needed calm during this very crazy time. If you’d like to check out more of Jenny’s work, you can visit her website here. Thanks for reading, and thanks to Jenny for this wonderful interview! Stay safe, Louise Robert Villamagna is a West Virginian mixed media artist, known in our shop for his metal paintings. His bold colors and comical compositions sit proudly on our walls in the gallery space. I had a fun interview with him that I hope you enjoy reading! As someone who has very little knowledge about metal working, I first asked Robert about his material process. “I would estimate that about 75% of my ideas start out in one of my many sketchbooks. From there I usually create a rough sketch directly on my support (wood panel, medium-density fibreboard panel, or a found support such as an old desk drawer) using a Sharpie. Then I begin searching the studio for materials...which may take a few hours or several days. [Then] I begin putting the actual piece together...I may spend days, or even weeks, on a piece. My tools primarily consist of tin snips, hammers, various fasteners (nails, rivets, industrial adhesives), and power tools...My work may be classified as 2D, but in many cases it falls into a 3D category. It all depends on what and how much material or objects I am attaching to the plane or support. At a certain point the work does become frontal sculpture.” The metal works produce a bas or low relief effect. A bas relief is a sculptural technique in which the artist carves or chisels away at a material to create an image that is basically a sculptural painting. The piece is frontal like a painting, unlike other kinds of sculpture in which the viewer can move around the object and view the piece from all sides. I find it ironic that his pieces are relief-like and yet are created using an additive rather than reductive process--he builds up the pieces by adding material to the surface rather than carving away at the material to make the image. This relation to bas relief is further enhanced by his subject matter. Traditional Greek and Roman relief pieces depict scenes of stories and myths, and Robert’s pieces also have a narrative quality. He spoke about this narrative quality and how he views it in his work: “The “stories” you refer to come from a variety of sources. A source may be a memory from my life, a line I’ve heard in a song, a piece of a conversation I may have overheard at the grocery store, or something suggested by the materials themselves. In many cases the story that I feel I am telling in a particular piece may not be the story that a viewer might “read” into one of my pieces. In most cases, I’m OK with that.” Robert mentioned that he normally sketches out his compositions before proceeding, though often these sketches act as more of a guide than a set plan, which is true for how he approaches narratives and stories in his pieces as well. I asked him about how much preconception goes into his pieces and how much he discovers along the way: “All of my work consists of exploring. That’s the nature of the materials I use. I may have a preconceived idea in most cases, but the actual building of the piece is based on lots of experimentation with various materials and found objects.” Next I asked him about the visual tools he uses in his work, namely composition and color. “I usually approach value first, color second. There are certain elements in each piece that I want to get attention, so looking at value is very important here. Color plays an important role, of course, but it may be affected by the subject of the piece, the mood I wish to convey, or what material colors I have on hand.” As a viewer, I see saturation and contrast as important to his works in addition to tone. He thinks about neutrals in his pieces and how they contribute to the figure-ground relationships in the works, playing with what he wants to stand out and what sinks back. In thinking about all these elements in his pieces -- narrative, color, composition, materials, etc. -- I asked Robert to go into detail about the creation of the two pieces we have in the shop, Drink Your Money and Of Like Mind. “Drink Your Money was created for an exhibition titled “Almost Level, West Virginia,” a reflection on environmental issues in our state. I had a vision for a glass filled with money, so the negative space was this: keep it simple, use dark values to pop the hand and glass, and keep it warm.” “Of Like Mind is just me playing, silliness meets surreal. I had these metal tire images and wondered how I might use them. When I decided on the man and bear encounter, it just became a simple task of seeing what materials I had on hand representing “outdoors” and in appropriate colors that would not take the focus off my two main characters.” Robert’s practice, like all of our lives, has been deeply affected by the COVID pandemic. I asked what adjustments he had to make due to the pandemic, and he told me “I probably put in even more studio time during the pandemic since we are not traveling, attending concerts, etc. While my wife and I had COVID in August, I made nothing for about three weeks. As my symptoms dissipated, I began going back into the studio. However, it was difficult at first. I could only put in 90 minutes a day and I would be exhausted. Over the next few weeks I would closely build that up to two hours, three hours, etc. Now I am back in the studio full time.” Lastly, I asked Robert what he is working on now, now that things have settled into more of a rhythm and he is (thankfully!) COVID-free. “Right now I am drawing a simple layout of our house lot so that I can present it to our local planning board. I want to place a 12” x 16” storage shed on our property to store metal and objects. I’m trying to free up more space in my studio. And I just completed my “Gimbels Series”, a group of twelve works, each using a printing plate from the advertising department of the Pittsburgh Gimbels store. I wanted to show these as a group, but it’s tough to do during this pandemic.” “Right now I have a bunch of things I want to pursue. A six foot Mothman figure. A piece based on an old photo of a young man holding a fiddle, his mom behind him in the doorway of a log cabin. I’m also thinking about doing some large abstract metal pieces. I love non-objective abstract painting and I’d like to see if I could pull that off in metal and found objects.” If you want to see more of Robert’s work and what he is currently creating, check out his website here. I’d like to thank Robert for taking the time to answer all of my questions so thoroughly and thoughtfully! Thanks for reading, Louise  Robert sent this picture of a piece in which he combines drawing and metal, a process he hopes to use again in other works. This one is titled "Siblings." Carla Markwart’s colorful pieces can be seen all around downtown Galesburg. She has painted a mural on the Box, near the Beanhive on Cherry and Simmons, in the entry to the Galesburg Commerce Center, and several of the trash cans scattered about downtown boast her handiwork. Carla is dedicated to the process of exploring and discovering with paint, taking the viewers on an exciting visual journey. I enjoyed writing this post about her art, and I hope you enjoy reading it!

Because color is so important to Carla’s work, I first asked her about the use of color in her pieces. She responded “I try not to plan my work too much. I like to choose colors that I don’t like or respond to...that makes the challenge. I like to make cool versions of warm colors, and warm versions of cool colors. I tend not to use much blue because blue is everywhere and everyone’s favorite color is blue. When I make these paintings, I don’t plan the colors ahead because that makes the process of painting so boring. The fun is choosing the colors and solving the problem of color placement. If the painter is bored, the viewer will be bored.” The idea of solving problems with color is one many painters use: examining the color relationships and how each one speaks to the other, solving and creating problems simultaneously to keep the painting open and engaging. Carla’s abstract compositions are equally important to her work and rely heavily on circles, a recurring motif. I inquired as to whether or not these circles have any particular meaning to her, and why they are the dominant force in her compositions. “In my recent paintings, I am limiting myself to circles and straight lines. A circle is a perfect shape; it appears in nature everywhere you look; and it's easy to draw! I start by drawing a bunch of overlapping circles, then bisect them in arbitrary places with lines, then erase some lines and edges to make bigger, irregular shapes. Sometimes I make the overlapping shapes a close approximation of the 2 colors combined that are overlapping...but usually I don't because that is too predictable. Every inch of a painting has to be interesting and surprising- especially with the compositional limits I have set myself. It is kind of an all-over composition; no obvious figure-ground distinctions…” It seems that the driving force in choosing her compositions comes from exploring with the color, lines and shapes-- it’s about finding compositions rather than preconceiving them. The phrase “figure-ground distinctions” refers to the flatness or depth of a painting. There is no real sense of deep space in Carla’s pieces, the shapes aren’t distinguishing themselves from one another as closer to us or further away, but rather all existing on the same plane. There is intense complexity in this painting strategy, because then the artist’s job (like Carla says) is to make the painting interesting to look at without using the tool of differentiation through space. Instead, the differentiation comes from scale, color, and composition. Achieving these precise shapes and sharp edges is no easy feat. Carla uses a compass and straight-edge to draw the designs on paper or brick. “Then I just paint the shapes. I have a pretty steady hand and I don't have the patience to use tape. And I like the paintings to look like they were handmade.” I find it amazing that she doesn’t use tape to achieve the sharp edges. The handmade quality she’s interested in accomplishing is what is awarded to the viewer once they examine the work closely after being struck by the neatness of the shapes. I enjoy this interplay between the idea of precision and handmade, they seem to exist in different worlds with different goals, but Carla seeks to combine the two, and it works! Next I asked specifically about her mural work, as well as its relationship to her smaller works on canvas and paper. “My studio paintings had been getting bigger and bigger, so murals were a natural next step. My simple geometric shapes are a good fit for huge walls...I guess I like extremes. Either tiny paintings or very large ones. The large ones envelop the viewer and the little ones draw the viewer in. I don't make many middle size paintings- maybe that is my next challenge!” In terms of the relationship between her mural works and smaller pieces, she told me “The small paintings started as studies for murals, so they definitely have things to discuss with one another. I like to work on several at once. When one becomes frustrating, I can move on to another- different- frustration. The satisfaction comes from working through the problems I set for myself.” It is amazing that she is able to so fluidly switch from one scale to the other, seamlessly adjusting to the compositional challenges each size presents. Carla sees her paintings as “joyous, a little bit humorous, perhaps a little too simple, but in their simplicity is a kind of restfulness.” I would agree, her murals certainly fit in the settings they are, becoming almost site specific in their ability to transform the space while still remaining true to its function. They bring a pop of color, brightness, and joy to the places they inhabit. I’m excited to see where she paints next! If you’re interested in seeing more of Carla’s work, including her earlier work that departs from abstraction, click here to visit her website. Thanks for reading! If you need a pick-me-up, stop by our shop to check out Carla’s smaller pieces, or take a walk downtown and look around--they’re sure to brighten your day! Best, Louise Paulette Thenhaus is in the business of color, emotion, and nature. Her work seeks to evoke feelings of happiness and comfort, something she thinks isn’t given enough weight in the art world today. She is committed to and passionate about painting landscapes in the midwest, which certainly shows through her pieces! I was fortunate enough to have a phone call with her about her process and other projects she has in store, I hope you enjoy it!

Initially I asked her to tell me about her plein air practice. For those who don’t know, plein air literally translated means “open air”, and refers to landscape painting on site, or on location. This kind of painting means you are at the mercy of the weather, temperature, and other natural elements that can influence a piece. For this reason, every plein air painter has their own tricks and specific methods when going out into the field. I asked Paulette about hers, and she told me about the materials she uses and the time frame in which she paints. She primarily uses acrylic paint, as she likes how quickly it dries and enjoys the immediacy in seeing the final product. Because of it’s quick-drying nature, this also means that Paulette is outside for an hour to an hour and a half painting with short, open brush marks. Most of the time she completes the paintings out in the field, but if need be, she’ll bring them back to her home studio to finish. She normally brings smaller canvases out into the field, typically sized at 16 x 20”. She told me she likes to try and put the temperature, textures, colors, and scent of the location in her paintings, wanting it to feel as real as her experience in the place. The smell aspect is particularly important to her, and to communicate it through her paintings she relies on color, texture, and brush marks to translate the aromas. These elements of color and texture change based on what season she’s painting. During the warmer months, Paulette is able to stand outside with her composition and paint, but during late fall and winter she tends to paint from the view of a window, tucked inside her house or car. Before settling on a composition to paint, she walks around the site for a bit, observing what sparks her interest. She typically goes outside to paint when she’s feeling positive about the day, as she prefers not to paint when feeling negative or grumpy. Her interest lies in making people happy, upbeat, and positive while looking at her paintings. This is achieved through her color combinations, particularly her use of complementary colors that have high contrast and make the pieces pop, immediately drawing the viewers’ eyes to the piece, much like the immediacy with which she paints the scenes. She wants to create paintings that are easily felt and accessible for all to enjoy and bring a positive experience to. The complementary color combinations also reflect the season and (some) the time of day. She noted her painting "Dusk" as an example, directly reflecting the time with soft grays and blues. Then there are the paintings done in the bright sunlight, which use more saturated colors. Every now and then she makes a night painting, and likes to paint in a variety of weather. In particular, she is interested in what happens when natural elements find their way into the painting, as they directly reflect her experience outside-- they help the painting remain “in the moment” of its creation. Paulette’s goal with these paintings is to recreate the experience of being in the place and not rendering the place as it’s seen. She referred to Van Gogh’s paintings as inspiration with their emotional saturation: each brush stroke and color represents his feelings being in the landscape, the light and temperature reflective of his experience as well. Like Van Gogh, feelings and colors decide her compositions, what she “sees and feels determines what she paints.” We talked a bit about some non-landscape pieces she has made, specifically the big gold piece hanging in our gallery space called "Autumn Glow". For this piece and several others, she created stencils before applying paint. In the case of “Autumn Glow” she spray-painted gold over the stencils, which was superimposed over a pink-hued fall scene, a scene whose composition was created entirely in Paulette’s mind. Her goal was to make both the gold and the autumn scene peeking out from behind the leaves, which inspired the creation of the composition. In general, Paulette’s pieces really do glow-- her color combinations catapult me to a world filled with rich light and textures, an upbeat, dream-like space. Not a bad place to rest during the craziness of the world right now! Paulette is currently working on self-publishing a book titled “Drawing From Life, Adventures of the Midwest.” She was inspired to write this book due to her experience in New York as an artist, when she entered a cowboy piece into a juried exhibition called “Is there Art in the Midwest?”, poking fun at what New Yorkers thought of midwesterners, and responding to the title of the exhibition with “is there nature in New York?". We remarked that there is indeed a lot of art in the midwest, as the landscape inspires people to depict the rich beauty here. We hope to have access to Paulette’s book once it comes out, and are thankful to be a space where she shows her wonderful pieces! If you are interested in Paulette’s work and want to see more, check out her gallery page on her website, which you can access here. Thank you for reading! Best, Louise You might recognize the Galesburg native Christopher Reno’s work from our gallery, particularly the biggest piece of his we have on the wall facing the window of our gallery space. Many have marveled at the piece’s scale-- the largeness of the canvas compared to the minute dots layered preciously over its surface. His pieces are truly astounding, such a meditative air and obsessiveness exist simultaneously within the careful dots he constructs, senses of calm and mania imparted at once to the viewer. I was fortunate enough to ask him some questions about his work, and a lovely conversation unfolded, which I hope you enjoy!

My first inquiry was regarding the perceptions surrounding his work-- the way these pieces make him feel, his motivation for constructing such surfaces, and what he hopes others feel from his work. He responded by establishing a connection between his work and the work of Agnes Martin, a prominent abstract American artist, active from the 1940s through the early 2000s. The two share a meditative and inward quality to their work, both focused on pattern, abstraction, and repetition. Chris said “I love the transcendent serenity that she achieves through obsessive manipulation of the grid. I share some of that obsessiveness but I’m also willing to let the grid fail and sag…In fact I’m most drawn to this tension - will the piece fail? Is it just a bad painting? Can it transcend its homely appearance and process?” Chris hopes that people are relieved when they look at his work, but “can also just as easily imagine that they would make people annoyed and perplexed.” Chris’s interest in transcendence and time is integral to his work. The process itself relies heavily on a long amount of time, and the relationship between the work and the viewers is in conversation with that lengthy process. I can get lost in the pieces for minutes, hours. Often, measuring the time spent discovering the work becomes insignificant once I’ve fully given the pieces my attention! I asked about the time aspect of his work, and he said “They take a while to make, but because they are like a hobby it doesn’t really matter. I can do them whenever I want...It’s a very similar thing to my Mom’s hobby of knitting/quilting/crocheting...She made the work for the simplest of reasons, because it gave her pleasure and it helped her occupy her time with something creative and pleasant. There wasn’t a deadline, there was a process. What could be better and more poetic? It’s actually a great relief to find a process that is simple yet rewarding...I’m continuously surprised by what comes out of it.” His connection to Agnes Martin through pattern and repetition is shown through his use of materials--the textures and colors he uses--but departs through his appreciation for letting the grid go and moving through the “flub-ups” by incorporating them into the piece. He thinks a lot about pattern, texture, and color throughout his process. “I love painterly painting from the New York school - de Kooning, Guston, Pollock. My oil paintings are chunky and gooey on purpose...I want them to have a texture like woven cloth. I like the idea of a painting being like a textile, or that I’m weaving with the paint. And with the watercolors, I like bleed, drip and handmade wrinkly paper. I like the flub-ups and blobs and I like to weave them in.” As for his color palettes, he said “I choose [them] at the outset and modulate them very carefully throughout the process, but I don’t have any endgame. I just follow a careful process and see where they go...eventually the strategies and processes exhaust themselves and it’s time to move on to a new piece...If I’m not happy with where the painting is at that point, I’ll partially destroy it by painting over areas, or sanding and scraping the work down, to look for new possibilities.” Lastly, I asked him about the importance of words in his work, namely in his titles, as they often address something so specific, such as the titles “It All Comes Apart” and “Lemon Scented Radiance”. How do the titles and pieces themselves relate? Chris replied “The titles come spontaneously. Sometimes they are a clue to the origins of the work and sometimes they are simply associative because they came to mind while working. I like when they have a poetic, opaque quality to them...sometimes the work is inspired from a source - a song, a picture, or another artist.” Chris has most recently been working on nature photographs printed using a plotter and sharpies. He said these pieces relate to Agnes Martin in their adherence to the grid and the buildup of material, though they are “the objects I make that are most loyal to the source imagery.” The pieces are made from 30-40 layers of various spot colors, and they take a long time, a very patient process indeed! “Each color takes from 4-8 hours to draw. That's why there are only 5 of these new ones because they each took weeks to create.” You can check out this most recent body of work as well as the paintings on his website by clicking here. Thank you for reading, and thank you to Chris for this wonderful conversation! Best, Louise |

AuthorLouise Rossiter writes about artists featured in our shop! Archives

April 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed